About Labyrinths

Below, you will find information and many links to articles, organizations, books, journals, podcasts, online forums, YouTube videos, social media groups, and other sources of information that may be useful as a starting point for finding out more about labyrinths and labyrinth walking. Simply click on the item in the list below that you want to view.

![]() About the labyrinth

About the labyrinth

![]() History

History

![]() Types

Types

![]() Finding a labyrinth

Finding a labyrinth

![]() Approaching the labyrinth

Approaching the labyrinth

![]() Benefits and Research

Benefits and Research

![]() Organisations*

Organisations*

![]() Journals*

Journals*

![]() Books*

Books*

![]() Articles*

Articles*

![]() Podcasts*

Podcasts*

![]() DVD's*

DVD's*

![]() YouTube Videos*

YouTube Videos*

![]() Social Media*

Social Media*

![]() Labyrinth Locators*

Labyrinth Locators*

![]() Patterns and Templates to download*

Patterns and Templates to download*

![]() Other helpful sources*

Other helpful sources*

* Links to English language listings, with indications of non-English translations for the listed items, where relevant.

About the Labyrinth

Labyrinths have a magical appeal – to walk one is not just to take a leisurely stride, as you might do when walking a dog. All manner of emotions can come to the surface when stepping onto the labyrinth’s path – along with fresh ideas, meaning-ful reflections, and inspirations for courses of ac-tion that you might take when you step back outside again.

The labyrinth is an ancient archetype, a secret known to our ancestors across many centuries. To walk one requires no qualification or previous experience. Young and old (and those somewhere in between); rich and poor; Hispanic, Native American, and Anglo-Saxon; Jew, Muslim, Christian, and Hindu; able-bodied and physically challenged; atheist and agnostic; city-folk and country-kind – the labyrinth invites anyone and everyone to step into its path, without judgment, and treating everyone as an equal.

The labyrinth is a single path that leads anyone who walks it toward a centre – unlike in a maze, there are no dead ends or blind passageways for getting lost. The path may be painted, cut into grass, marked out with stones, be paved with polished marble, or countless other ways. Labyrinths can be permanently laid out, or be temporary (mobile labyrinths, often painted on a canvas or other material, can be packed away and moved from place to place). They can also be of virtually any size, including small ones that you can sit on your lap for tracing with your finger.

Labyrinths can be found in many parts of the world, and have a long history. Common patterns etched into the ground, paved in stone, or scratched out on walls have been discovered in many locations. As a nearly universal and ancient symbol that seems to have a powerful positive affect on anyone that encounters it, the labyrinth is often referred to as an 'archetype', or something that speaks to us at a level that's hard to logically explain.

Labyrinths have been particularly popular during different periods in history. Labyrinths feature in many Roman mosaics, while by the 13th century C.E., they had been incorporated into the floors of a number of northern Europe’s great cathedrals.

Grass labyrinth in Massachusetts, USA

Photo © Carol Maurer

Labyrinths are not owned by any one culture or religion. Ancient examples are found in most continents, although their purpose remains a mystery. Labyrinths have certainly been used for ceremonial purposes, as well as serving as gathering places. Most commonly, they have been used for walking (in earlier times, often as part of a pilgrimage, but now, most normally for meditation, reflection, and a simple escape from the busyness and concerns of everyday life).

There are now thought to be over 5,000 labyrinths in the United States alone. Many of these are portable labyrinths, painted onto a canvas mat or some other material. This idea owes much to the work of Rev. Dr. Lauren Artress, who popularized the use of a canvas labyrinth at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco in the 1990s. The portability of this innovation became immediately popular, and spawned the creation of hundreds of similar foldaway labyrinths across the USA.

Many permanent labyrinth installations have also been created. Clubs, churches, temples, hospitals, town squares, public parks, prisons, and schools are among the many places that labyrinths can be found.

Click here to return to top of page.

History

Labyrinths have a very long history. We simply don’t know how ancient this history is, and fresh discoveries are still being made.

A famous tale from Greek mythology tells the story of the Athenian Theseus, who with the help of a sword and a ball of thread gifted to him by the lovestruck daughter of the Cretan King Minos, Ariadne, manages to overcome a fearsome monster that’s trapped at the center of a supposedly inescapable labyrinth. After defeating the Minotaur, Theseus retraces his steps by following the thread that has unraveled on his inward journey, the other end of which had been tied at the labyrinth’s entrance. The pair then flee to the island of Naxos, leaving Minos in a fury, and vowing to punish the labyrinth’s creator.

This labyrinth was designed by Daedalus, an ingenious inventor, as a means for housing the Minotaur, which Minos was ashamed to present as his son. Each year, seven young men and seven young women were sent from the mainland as an offering to satisfy the Minotaur’s insatiable appetite. Following Theseus’ solving of the labyrinth’s riddle and overpowering the Minotaur, Daedalus attempted to flee Minos’ kingdom, but the furious king banished him to an impregnable tower as a punishment for his supposed assistance for Theseus. We encounter him again in the story involving his son Icarus, who famously flew too close to the sun, causing the melting of the wax on the wings that his father had made for him as a means for escaping their imprisonment in the tower.

Daedalus’ ‘labyrinth’ may be what we now call a ‘maze’. It may have included many dead ends and crossroads, designed to keep the Minotaur safely imprisoned at its center, as well as to trap anyone who dared to wander in. However, Theseus found the one true path–the labyrinth–which doesn't set out to ensure or fool those who tread its path. Modern puzzle mazes incorporate the same principle–for those who know their secret, there is a single, if complicated, path to the center.

Various civilizations are known to have used labyrinths labyrinths around the same time as the Greeks.

For example, the story in the epic Mahabharata of Abhimanyu, son of the great warrior Arjuna, tells how the young man is taught how to make his way onto the battlefield and shown how to defeat his enemies, but not yet how to return. The tale is depicted in Hindu lore as a labyrinth, which bears a striking similarity to the Classical style, albeit being a distinctive variant of the pattern.

The Hindu version, known as Chakra-Vyuha (literally, ‘wheel-battle formation’), represents the arrangement of troops in a labyrinthine pattern. It is found in numerous reliefs, as well as in Hindu, Tantric and Jain literature.

Ancient labyrinths were typically marked out in stone on the ground, or formed a motif in a floor mosaic; garden mazes with hedges appear to have been an invention of the later Renaissance period.

Chakra-Vyuha labyrinth

In contrast with a maze, a labyrinth has only one path (at least normally). Even where two or more paths are offered as a means of entry–as is the case with some specially designed labyrinths–any path that is followed leads to the labyrinth’s center. This is the point: there is nothing to worry about, except to follow the path, and trust that it will take you to where you need to go.

Theseus’ defeat of the Minotaur is thought to have been regularly enacted by the Greeks and later by the Romans in the so-called 'crane dances' around a labyrinth, also recalling the Greeks’ triumph at Troy, and so also known as the ‘Game of Troy’. This gives us a further example of the uses to which labyrinths have been put–for ceremonial and celebratory purposes. Some early Christians adapted the myth of Theseus to portray the perils of hell that face those who don’t follow the single path. Their encounter with the center was to be devoured, not saved. However, it’s fair to point out that Christians also believed that the labyrinth is an allegory of the soul’s path toward a New Jerusalem, and that only the unfaithful could expect their journey to end with a descent into hell.

Generally, from the time of the Romans onward, labyrinths have been considered a space for protection. They are a safe space that holds us, even as we come into touch with our inner lives. The same is true of standing stone circles, forest groves, and circles of people–all are seen to contain a positive energy, being held by a spirit of compassion.

Happily, the labyrinths of today usually have no Minotaurs pounding the ground at their centers. Rather than being spaces that overwhelm us, they are places for discovery and growth. As labyrinth historian Hermann Kern so aptly says: “In the labyrinth you don't lose yourself. You find yourself.”

The Classical form of labyrinth (not the type that sets out to ensnare) is a pattern that's often found today. Similar patterns have been found in labyrinths discovered in North America and India.

Examples of Classical labyrinths, cut into sand, and made of stones

in a garden

Examples of the Classical pattern can be found in Jain, Hindu, and Buddhist manuscripts, as well as designs seen in Java, Nepal, and Afghanistan.

Labyrinth petroglyphs (rock carvings) in Galicia, north-west Spain, are thought to date to the early Bronze Age, and labyrinthine patterns found on old Babylonian tablets can be dated with reasonable certainty to around the same period. Early Etruscan examples have also been found.

What is clear is that labyrinths have a very long history–longer than recorded history itself.

Many mosaics from the Roman period incorporate elaborate labyrinth patterns in their design, characteristically representing an angular path, which is completed in a sequence by moving from one quadrant of the floor area to another.

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder (23/24–79 CE) includes a list of architectural labyrinths in his ‘Natural History’, suggesting that labyrinths had more than aesthetic appeal for the Romans.

The Austrian traveler Gernot Candolini recalls one explanation for this particular labyrinth’s significance from a man that he met at this sacred place: “‘The labyrinth is the belly of the mother’, the man asserted, ‘the umbilical cord leading to the earth’. ‘It’s the dance of the women’, said a woman, ‘and you men will never understand it’”. If it’s true that the labyrinth is “a symbol of the Earth, the womb of the soul, and a dancing ground”, as another observer mentioned, we can fairly say that the labyrinth has a powerful role to play in connecting us with the very ground upon which we walk, the provider of everything that we eat, and which offers us a sure base on which to build our homes–the home that some call Mother Earth, or Gaia.

The history of labyrinths in the Americas remains a largely untold story. Drawings have been discovered in South America, while references among Native American peoples span several centuries. Labyrinth rock carvings are found in the south-western United States–notably in New Mexico and Arizona.

The concept of the labyrinth as Mother Earth, the giver of life, is seen in many Native American representations. Spiritual rebirth, and the process of passing from one world to the next, are also considered important in the labyrinth’s symbolism for the Tohono O'odham people.

Notable variations to the classical pattern are found illustrated in Native American petroglypgs and basketwork, including a square labyrinth with two entrances, and a pattern that combines both the familiar circuitous path of the classical labyrinth, along with what appears like a ‘spider leg’ distortion (see the diagram below).

In Europe, the labyrinth at the Cathedral of Notre Dame at Chartres in France (about 80 miles south-west of Paris) is particularly well-known. The labyrinth that can still be walked there today dates from the thirteenth century.

The cathedral was for many centuries an important destination for pilgrims. Visitors included those who were unable to journey to Jerusalem; the labyrinth instead offering a symbolic focus for a pilgrimage.

Many are said to have walked the stone tiles of the labyrinth following long and arduous journeys to reach the hallowed town, with its imposing cathedral looming into view many miles before they reached their destination. For a pilgrim, to reach the center of the labyrinth at such a great cathedral was to arrive at the New Jerusalem.

The design of the Chartres labyrinth is strikingly beautiful. Set into the pattern are 112 lunations, or ornamental motifs that mark the labyrinth’s outer-border. With near perfect symmetry, the labyrinth is as much a testimony to the grandeur and masterwork of this outstanding cathedral, as are the many stained glass windows that shine into its great space, including the exceptional rose windows that bathe the north and south transepts, and the intricately crafted sculptures that adorn its exterior.

It’s often said that the great rose window at the western end of the nave would transpose exactly onto the plan of the labyrinth were it able to be levered from its vertical plane onto the floor of the cathedral. However, the eminent labyrinth historian Jeff Saward has disproved this theory. Nevertheless, mysteries about the meaning of the labyrinth’s design continue to engage scholars, some suggesting that it may once have provided a space for enacting a ritual using a ball, others speculating that it may have been used as a calendar, to help calculate the date of Easter.

The masterpiece at Chartres is one of a number of cathedrals, abbeys, and prominent churches surviving from the medieval period in Europe that are known to have been home to a labyrinth.

Elsewhere in Europe, labyrinths can be found in alternative settings, and–as far as we can tell–were used for differing purposes.

The Medieval labyrinth at Grace Cathedral, San Francisco

and canvas Baltic Wheel labyrinth

Around the coast of Scandinavia, for example, more than 600 labyrinths formed of stones have been found at locations that have become known as 'Troy Towns'.

The labyrinths in Scandinavia all follow the classical or a spiral-based classical style. A variation to the design is found in labyrinths that have been found on the southern coastline of the Baltic Sea and in German-speaking countries of Europe, now commonly known as the 'Baltic Wheel' style. The proximity of the Scandinavian labyrinths to the coast suggests that they were important gathering places for fisher folk.

Today, labyrinths appear to be more popular than ever before. It’s thought that more labyrinths have been created during the past thirty years than throughout all other human history. To some extent, this might not be surprising – the world population has grown exponentially over the past hundred years or so, and of course, we have more effective means for producing portable artifacts and communicating information about them than had our ancestors.

In her book 'Walking a Sacred Path', Rev. Dr. Lauren Artress describes the unprecedented interest in the labyrinth at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, which was first opened to the public just before New Year’s Eve, 1991.

Such was the popularity of the labyrinth at Grace Cathedral, that Rev. Dr. Artress was soon asked to bring her ministry of labyrinth walking to many others across the United States, as well as around the world.

The great innovation with the Grace Cathedral labyrinth was the use of a portable canvas–one that could be taken from place to place, being laid out as required, and then folded away again to allow the space that it occupies to be used for other purposes. Partly through Lauren Artress’ calling, and the earlier inspiration of New Age teacher Dr. Jean Houston, the labyrinth came to be re-established as a well-known space for healing, meditation, reflection, community building, peacemaking, and many other purposes.

Find out more about the history of labyrinths

Labyrinthos, an organisation founded by labyrinth historians Jeff and Kimberly Saward, is the home for learning about the history of the labyrinth. Its extensive website of articles and photographs is supported by two annual journals, including Caerdroia, which publishes scholarly papers and research articles. Labyrinthos offers a wonderful treasure trove for discovering more about the labyrinth, and we recommend a visit to their website. Click on the following link to go there: Labyrinthos.

Click here to return to top of page.

Types

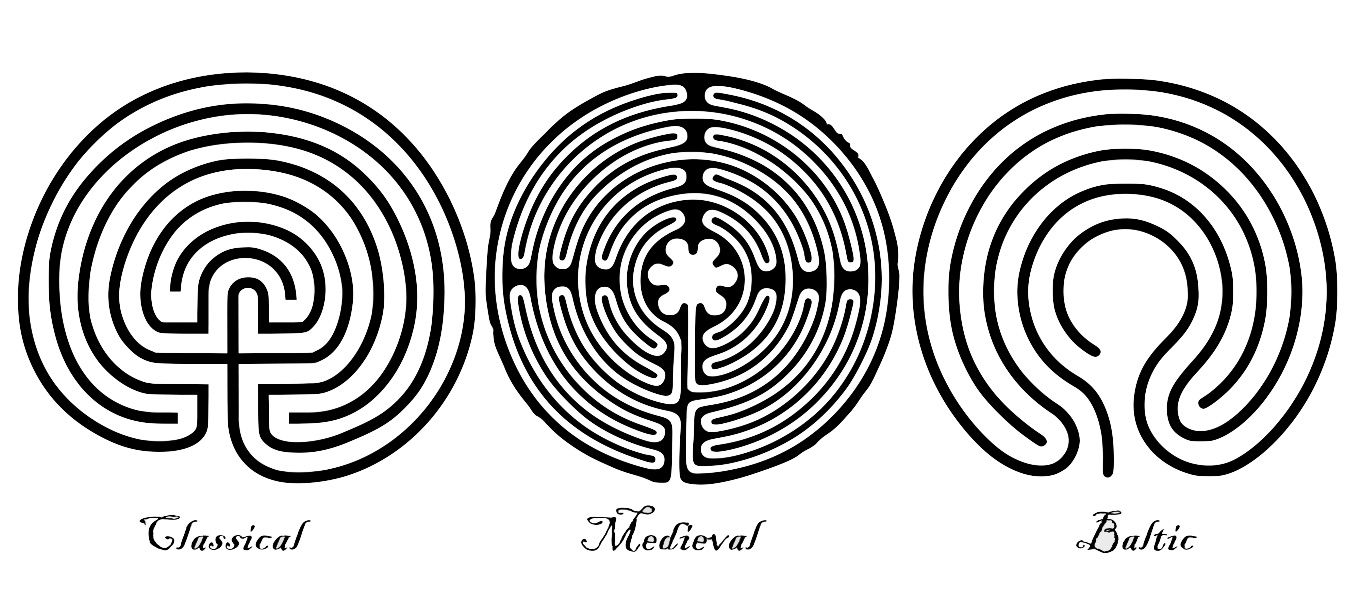

Labyrinths come in many shapes and sizes. Some have suggested that different patterns can have different affects on the people that walk them–that they tend to prompt different feelings, or bring different things to mind. In some cases, it seems that labyrinths had been designed with a particular purpose in mind.

Labyrinths aren’t always circular in form, neither are their paths always smoothly sinuous. The installations at the cathedrals in Amiens, France, and Ely, UK, for example, display a very angular pattern. Nevertheless, a well-defined perimeter contains these and all labyrinths, and it will be apparent to any walker who walks them that they are moving around, and ultimately toward a center.

Many labyrinth designs, such as the familiar pattern seen in the medieval style, involve frequent turns that take us back in the direction from which we’ve just come. An ingenious feature of the medieval (including the Chartres) pattern is that its sinuous path at times comes close to the center, and then takes a walker away toward the outer edge again.

A so-called "processional" labyrinth, for example, has a different path leading into the centre than the one leading out. The"Baltic wheel" is one such type of labyrinth. These allow for a “procession" of people to walk through the labyrinth, without people needing to pass by others walking in the opposite direction. They lend themselves to ceremonies where such a procession is intended.

Elsewhere, there may be far more practical reasons for designing labyrinths the way that they are. Routing a path around a tree, or fitting one into a particular shape and size of available land, are examples.

Labyrinth paths have also been drawn to map out a logo on the ground, to be used for special purpose, such as in conflict resolution and reconciliation, or simply to be artistically creative and pleasing.

The Classical, Medieval, and Baltic Wheel patterns of labyrinth are perhaps the most commonly found.

Others, such as the "Man in the Maze" type, are also well-known.

What is interesting is that what may not appear to be a particularly obvious pattern to draw, notably the Classical type, shows up in many designs of labyrinths that have been found in different locations throughout history. It seems that the different people who created these had discovered some special knowledge or inspiration. However, this remains a mystery!

Other types of Labyrinth that are quite commonly encountered include the Santa Rosa, swastika, and Roman ‘meander’ type. Download Jeff Saward’s paper, ‘Mazes or Labyrinths… What’s the difference & what types are there?’ for more information.

Click here to return to top of page.

Finding a labyrinth

It may be that you’re fortunate enough to have a labyrinth in your neighborhood – one that’s permanently available in a park or city square, for example, or a portable version that’s regularly laid out in a space that's open to everyone. A simple Internet search should identify whether a labyrinth exists nearby.

One excellent online resource that’s specifically designed to help connect labyrinths with people that want to walk them is The Worldwide Labyrinth Locator (https://labyrinthlocator.com/). This extensive resource, sponsored by Veriditas and The Labyrinth Society, provides a searchable directory of hundreds of labyrinths worldwide. With just a few simple clicks, the website will list any labyrinths that can be found in a particular locality.

Click here to return to top of page.

Approaching the labyrinth

There is no "correct" way to walk a labyrinth

Every time we step into the labyrinth, we should expect to have a new experience. This is a little like life itself–every time we embark on something new, we can’t fully anticipate what may happen.

Some people normally like to take a question with them into the labyrinth, something that they are seeking an answer for. But this isn’t always the case. Holding a question open or a reflecting on a word, quotation, quality or some other point of focus during the inward walk to the centre is common, opening yourself to receive whatever answer may come. A response to a question posed may not come immediately, but often an idea, a word from my inner voice, or a feeling does come.

Others aim to keep their focus on how they’re taking each step as they move forward. Here, the invitation is to pay attention to how our feet make contact with the ground as we take each step–being conscious of how we flex each leg as we take one step forward, then bringing the heel of the forward foot into contact with the ground, before arching the whole sole of the foot, and finally making full contact with the earth below.

Still others may wish to recite a mantra–a single word or simple phrase–as a means for anchoring their attention as they follow the labyrinth’s path.

Others just aim to calm their busy thoughts, and just be as empty or open as possible to what may come.

There is, simply put, no one right way to walk a labyrinth, other than to just follow the path!

Simply put: there is no one common experience that accompanies every walk. Many varied experiences may be encountered by different people at different times, as well as by the same person on different walks. Every walk happens for the first time. Every walk is unique.

If you are at a walk that is being hosted by someone, rather than walking a labyrinth that’s accessible at any time, the host of a walk may typically suggest some guidelines to follow, both before and after walking, and when moving around the labyrinth itself. These may include such things as respecting the space and silence of others.

Generally, being silent as you walk seems helpful. However, some like to sing, dance, wave their hands, practice yoga postures, and many other activities too (or stopping along the way to do so, including stepping off the path they are on for a moment to pause, kneel, or do whatever feels right).

When you are ready to begin your walk, step over the threshold of the labyrinth and enter into its protective space.

Walk at whatever pace seems right. The movement along the path isn’t a race. You may like to keep ‘soft eyes’, or a gaze that isn’t too firmly fixed on anything in particular (we are grateful to Lauren Artress for introducing this idea to the labyrinth community). You may not want to think about arriving at the center, and it doesn’t matter whether or not you reach it.

Your pace may quicken at times, and slow down at others. Sometimes, you may feel that you just want to rest awhile. Some labyrinth designs, such is the Chartres design, offer points where it’s possible to step off the path of the labyrinth for a short while. These features, such as the double-headed axe shape (what's known as a "labrys") seen in the Chartres pattern, are spaces where it’s possible to stand, sit or kneel for a while, without interrupting the passage of other walkers.

Some like to rest a while at the center

of a labyrinth

At the center, you may wish to rest for a while. The center is a place of integration: a place to stay awhile and be absorbed by what is happening all around. This is, as Virgina Westbury puts it, “[a place that symbolizes] wholeness and completion, the heart of the matter, our human heart”. When you are ready, return along the path that brought you to the centre (or via another path, if you are walking a labyrinth that offers a separate way out).

It’s often said that the labyrinth is a metaphor for life–that people are following their own life paths, but that we are all moving toward the same destination (to realize our full potential as individuals, to be saved from the tribulations of everyday life, or to find enlightenment). During life’s journey, of course, we encounter others–sometimes coming toward us, sometimes passing us by, and at other times just featuring on the periphery of our attention. Such encounters happen in the labyrinth too, but without involving an exchange of words or–at worse–a crossing of swords.

We don’t know what others may be experiencing during their walks, what thoughts may preoccupy them–all we are aware of is that we are each going forward, at our own pace and in our own way.

If the labyrinth models life in the everyday, then it can also be thought of as representing the full cycle of life–from birth at the entrance way, through to ‘dying’ to old ways of thinking and behaving at the center, and then emerging from the labyrinth as though reborn.

By the way, no qualifications or experience are needed to walk a labyrinth! Labyrinths are equally relevant for people of faith or who consider themselves to be “spiritual”, and for those who aren’t. The labyrinth invites anyone and everyone to enjoy its embrace and mystery.

Click here to return to top of page.

Benefits and Research

Today, many people walk labyrinths to meditate, reflect, or detach from the everyday for a short while. Many people report feeling inspired, uplifted, or having flashes of inspiration. Most commonly, many discover a sense of peace when walking a labyrinth. Were it to offer nothing else, the labyrinth offers a safe space where you can be at one with yourself, not demanding anything from you other than that you put one foot in front of the other, and breathe!

An increasing body of evidence supports the healing qualities of labyrinth walking. In an examination of published research, Dr Herbert Benson of Harvard Medical School’s Mind/Body Institute is convinced that such practice leads to both reduced blood pressure and improved respiration rates. Chronic pain, anxiety, and insomnia, are among other conditions that available evidence strongly suggests are reduced through regular walking of a labyrinth, quite apart from the obvious relaxation benefits.

In a similar vein, an extensive review by John W. Rhodes of 16 studies that had explored the positive affects of engaging with a labyrinth adds weight to the suggestion that labyrinth walking offers many potential benefits.

At the Myanmar Institute of Theology, for example, a labyrinth was created by faculty, staff, and students, with the express purpose of fostering the spiritual life of the community. The labyrinth was laid out with a prayer that those who walked it would find a connection with God. Within a short time of it being completed, individuals began reporting incidents of healing as a result of walking the labyrinth’s path. One man who had been suffering irregular heartbeats reported that his heartbeat had returned to normal after his encounter with the labyrinth; a woman reported feeling 'lifted up' when she walked, despite having a weak heart and doubting that she had the physical capacity to walk the path.

A community-building focus has also been important for many groups and organizations where labyrinths are used–including labyrinths that have appeared in university campuses, hospitals, and in the grounds of corporate headquarters.

See also:

'Labyrinths: Ancient Aid for Modern Stresses' by Karen Leland (article)

'Benefits of Labyrinths in Healthcare Settings' by Robert Ferré (article, The Labyrinth Society)

The Labyrinth Society Research Resources (references to research and articles concerning the benefits of labyrinth walking)

Click here to return to top of page.

Supporting labyrinth lovers worldwide.